Delinquent electric bills from the pandemic are coming due – who will pay them?

The shutdowns and restrictions that governments have imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19 have made it hard for many households to afford basic needs. Thousands of Americans are struggling to pay monthly utility bills.

Utilities and policymakers recognized that services like water and electricity are essential to people’s health, safety and comfort. Since mid-March they have taken steps to keep those services coming.

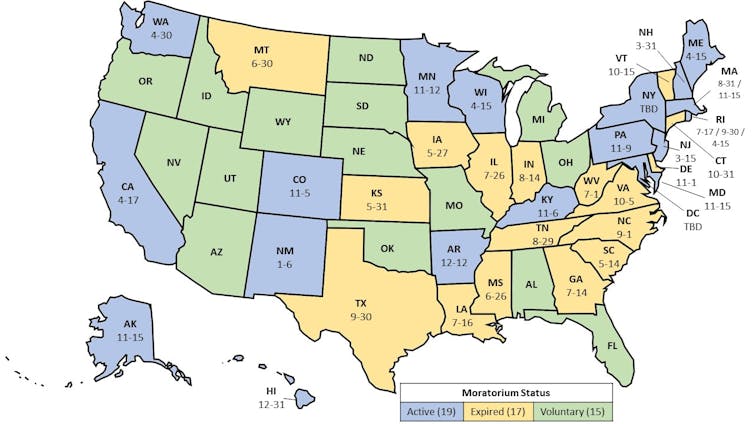

The most popular approach has been for them to impose moratoria on late fees and disconnections for nonpayment of bills. Every state in the U.S. has enacted some version of this policy, from formal declarations to voluntary programs offered by utilities.

But now these moratoria are starting to expire. Consumers are worried about whether their utility service will be accessible or affordable.

As director of energy studies at the University of Florida’s Public Utility Research Center, I’ve studied the impacts of COVID-19 policy on electric utilities, customers and regulators. These unpaid bills could affect many Americans’ lives, and in my view, there is no straightforward way to handle them.

A price tag in the billions

The National Energy Assistance Directors Association, which primarily helps states manage utility programs that assist low-income customers, recently estimated total unpaid electric bills as of July 31, 2020 at almost US$10 billion. This amount could grow to nearly $24 billion by the end of the year – equivalent to about 15% of what U.S. households spent on electricity in 2019.

And the challenge won’t end there. Moratoria in nine states including California, New York and Wisconsin, covering over 23% of U.S. residential electricity customers, are expected to extend into 2021.

Although this is a nationwide problem, there has been no concerted national effort to gather data on COVID-19-related utility debt. So far the most precise numbers are coming from formal regulatory filings in states like North Carolina and Indiana, and from informational workshop presentations.

So how will these debts be settled? There are four basic strategies, all of which have drawbacks.

Charge the delinquent customers

The first and probably most straightforward option is to directly assign debts to the customers that incurred them, usually through an additional charge on their future utility bills over the next 12 to 24 months. This treatment is most consistent with the principle of cost causality in utility regulation, which holds that the customer who caused the cost to be incurred is responsible for paying it.

Many utilities and the federal government have established programs to help people pay their delinquent charges and minimize the impact of these costs. But directly assigning delinquent charges to customers won’t work for those who are still unable to pay their bills, or who leave the system because their service has been disconnected. This means that any costs that cannot be directly assigned must ultimately be paid by someone else.

Charge all ratepayers

One possibility for “someone else” is the utility’s other customers – but only if the regulators who oversee that utility allow it.

Utilities work differently from conventional businesses that can set prices at whatever they think customers are willing to pay. Because utilities are delivering services that are deemed essential, they report to state utility commissions or local regulators. These authorities decide which costs of providing electricity or water are ultimately included in the rates that customers pay.

For example, when a utility builds a new substation or power plant, regulators typically allow it to recover the value of that investment from its customers over time. The total bundle of assets that a utility can recover from customers is called its rate base.

To add a new asset to its rate base, utility officials must appear before regulators and ask for the investment to be included in the rates that the company charges. The public can participate in these proceedings. After hearing from interested parties, regulators decide whether to include the value of the asset in rates.

If they approve it, then this asset is amortized over time, like a mortgage. The customers effectively make regular payments and pay interest – called the cost of capital – on the unrecovered balance.

So if an asset for this unpaid debt is created, it would be treated like any other investment and be recovered over time from all of the utility’s customers.

Turn bills into bonds

Some states have talked about securitizing these unpaid charges. This means taking a set of assets that can’t easily be converted into cash and turning them into a financial product.

One way this might work would be for a state government to issue bonds with a total value equal to the utility’s unpaid bills. The state would pay the proceeds from selling these bonds to utilities and repay the debt over time. This approach spreads the cost of unpaid electric bills over all of the state’s taxpayers, since the state would use money from tax collections to pay people who buy the bonds.

Make utilities take the hit

Some advocates argue that utilities should foot the bill for customers who can’t pay during the pandemic. But neither governments nor corporations have money of their own: Governments get it from taxpayers, and utilities get it from their customers and investors.

On the surface, requiring utility investors to absorb the cost of unpaid bills might seem like a clever way to protect customers. But the reality is far more complicated. First, as data from North Carolina show, a significant number of people in arrears are customers of municipal utilities, which are owned by cities and states, or cooperative utilities that are owned by their customers. These types of utilities don’t have outside equity investors whom they can ask for money to cover unpaid bills.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Other utilities are owned by investors, who provide the companies with capital in exchange for a risk-adjusted return on that investment. If the risk of the investment goes up, so does their expectation of their return.

If utility investors are asked to take on risks beyond what they perceive as fair, they may either require a greater return for their capital in the future – which would require the utility to raise its rates – or stop providing capital altogether and invest it somewhere else. This could affect the reliability and accessibility of utility service in the future. So while consumers might not pay today, they would likely pay in some way in the future.

Different states may choose to address this problem in different ways. What’s certain, though, is that the people – utility customers, taxpayers or investors – will end up paying for it. All that regulators and policymakers will decide is how and when.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.