The Good Fortune of Eugene Brigham

It was probably the simplest calculation Eugene Brigham would ever do.

There were two lines that day at the University of Miami. One was to register for law school. The other, for business school.

This was the mid-1950s. Law school was an established path. Business school? Newfangled and untried.

The law school line was long, and Brigham was in it. But the business school line “was a little ole short line,” says Brigham, in his honeyed southern drawl.

For a 25-year-old with no burning passion for either discipline, only a strong desire not to remain rudderless, the temptation was too great. He switched lines.

Finance research, business education, and the University of Florida would never be the same.

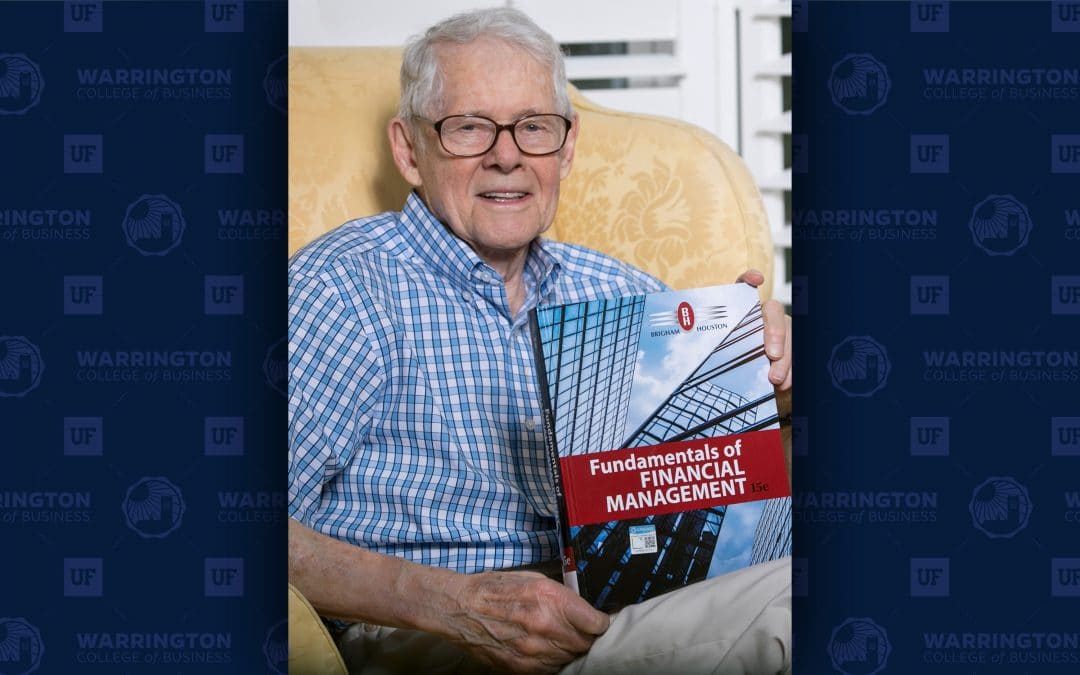

“What it shows is how luck enters into everything,” says Brigham, 88, in a modest accounting of a career that would include noted UF professor and benefactor, international expert on corporate finance, sought-after business consultant, founder of Warrington’s Public Utility Research Center, and perhaps most famously, name affixed to 11 finance textbooks, some spawning as many as 15 editions.

“People claim it’s being smart, but I think it’s luck.”

**

To say Brigham has sold textbooks is to say McDonald’s has sold hamburgers.

The publishing house doesn’t supply specifics, but they do say “the Brigham family of finance textbooks” — best-sellers, all — are used at over 1,000 universities in the United States alone and have been translated into 11 languages. Fifty years after Brigham penned Financial Management: Theory and Practice, Fortune magazine called it “the most durable finance textbook ever written,” making Brigham “one of the wealthiest B-school teachers ever.”

Look at Amazon and see breathless accolades not normally attached to books covering dividend yields, fixed assets turnover ratios and net present value profiles. “An excellent resource!” “One of the best financial management books that I have ever read.” “Simply amazing.”

The reviews, Brigham says, were once far from glowing.

The whole textbook saga owes its longevity to a cocktail of talent and temperament, but its start can indeed be traced to a stroke of good fortune: Brigham, who ultimately bypassed Miami to get his MBA and Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley, was hired at UCLA by a finance luminary who happened to have just written a textbook.

J. Fred Weston, who passed away in 2009, was by all accounts brilliant — a mentor to economists who would go on to win accolades of the Nobel variety. When Brigham arrived at UCLA in 1962, his boss had just released Managerial Finance, a textbook beloved by professors but, it’s safe to say, despised by students. Weston had a penchant for bypassing detailed explanations in favor of the phrase, “It therefore follows that ….”

“If you had an IQ of 180, it did,” Brigham says. “If you didn’t, it didn’t ‘follow that.’”

Weston’s extreme erudition combined with a general lack of enthusiasm for boiling down complex theories infuriated students. Hate mail was sent.

Brigham, teaching with his boss’ tome, began jotting notes explaining why exactly this followed that. After several semesters, his notes virtually amounted to a new book.

Weston’s publishing deal called for a revision in 1965, and he asked Brigham to take on the task. Brigham dove in, clarifying and adding real-world examples, and when the second edition of Managerial Finance was released, sales jumped ten-fold.

A textbook juggernaut was born.

Brigham, meanwhile, was also conducting academic research, penning scholarly articles and receiving accolades for his classroom instruction. Suitors, dangling enticing offers to excellent schools, began circling. UCLA parried, and in a scant four years — lightning quick for a top research university — Brigham was an associate professor with tenure. One head-spinning year later, he was full professor.

The next logical offer: department chair.

“That’s when I learned about the Peter Principle,” Brigham says.

More bothersome than the politics and personalities was being kept from the work he loved. So, when the University of Wisconsin came calling, he took his teaching skills, research, growing textbook empire and (Florida-born) wife to Madison.

Meanwhile, at the University of Florida, then-Dean Robert Lanzillotti was looking to bolster the reputation of UF’s business school. Coast-to-coast queries kept pointing to a “hot shot Ph.D.” named Gene Brigham.

“I was told, ‘I don’t think you’ll have a chance with him because Wisconsin made him a big offer,’” Lanzillotti recalls. He was undeterred. And clever. “I said, ‘Well, I’ll recruit him in January.’”

Sure enough, he brought Brigham and his wife, Sue, for a winter visit to Gainesville and offered a plum professorship, along with the promise of no committee assignments. There was no dragging Sue Brigham back to America’s Dairyland. The Brighams, including two daughters, moved to Gainesville in 1971.

**

Brigham can’t say for sure how his interest in finance took hold but growing up poor during the Great Depression definitely had something to do with it. As a young boy in Augusta, Ga., he had to care about money simply because he had to earn it. His father died when Brigham was 7 and the family struggled. “That made me not want to struggle,” he says.

Brigham eschewed studying through much of high school and had the miserable grades to show for it, but he was fleet of foot and became a state track champion. By his senior year, though, he realized college would be out of reach — and a life of struggle ensured — if he didn’t hit the books.

Improved study habits, raw intellect and, yes, fortuitous timing would save him. This was the late 1940s, and with the Cold War looming, the Navy needed more officers than Annapolis could produce. They promised a full ride to college in exchange for three years on active duty for those who could pass a rigorous Navy ROTC test. Brigham nailed the test and attended the University of North Carolina, where he distinguished himself on the track, including winning an ACC track championship. He graduated in 1952 with a B.S. in business administration.

He spent the Korean War on a destroyer in the Mediterranean, monitoring Soviet submarines coming out of the Black Sea. When his three years were up, family ties brought him to Miami, and the GI Bill® propelled him toward more college.

And then, that fateful encounter with the short B-school line.

All of this aligns with Brigham’s conviction that good fortune is the unsung force behind much of success. Sure, ability factors in, but too many successful people give too much credit to brainpower and too little to chance and circumstance. “The opportunities you’re given are luck,” he says, ceding that “whether you take advantage of them or not depends on you.”

He offers the formation of the Navy ROTC as an example. “Had I not done that,” he says, “then I would have gone to junior college and worked in the grocery store.”

**

In turn, Brigham’s arrival at UF, says Lanzillotti, should be counted among the university’s greatest lucky breaks.

Brigham “had a talent that is unbelievable, as a scholar, as an author, as a teacher,” says Lanzillotti, who helmed the business school from 1969 to 1986.

But even more transformational for UF, he says, was the cachet Brigham brought with him. When Brigham made the jump to Florida, the academic world took notice. Other young faculty set their sights on Gainesville. The business school’s spike in reputation, its subsequent rise in rankings across departments, its ability to attract top faculty and well-heeled donors willing to invest in business education — Lanzillotti traces those accomplishments directly to Brigham.

“Brigham coming to Florida was that spark that really lighted the way,” says Lanzillotti. “It really was a crowning act.”

The two shared a desire to increase the school’s visibility in the business community. Shortly after his arrival at UF, Brigham was asked to testify for the Communications Satellite Corporation (Com Sat) before the Federal Communications Commission. Lanzillotti supported this work and the many assignments that followed: Con Edison, Southern Company, General Public Utilities (during the Three Mile Island accident), Duke Energy, AT&T and others. Brigham would go on to launch the Public Utility Research Center at Warrington.

As it turns out, simplifying advanced business theories for judges — and ensuring explanations could hold up under days of cross-examination — meshed perfectly with teaching and textbooks. “I was practically writing textbook chapters when I prepared testimony,” Brigham says.

In the early 1970s, amid differences creative and otherwise, he and Weston parted ways. Weston took over the two existing books and Brigham created two new ones, which would go on to dominate the market. Today, there are seven “Brigham” textbooks. He worked on them solo until 1995, when he brought in coauthors.

One of those is UF professor Joel Houston, who occupies the Eugene F. Brigham Chair in Finance. Houston says uniting with Brigham to work on Fundamentals of Financial Management, now in its 15th revision, “was one of the best things I ever did.” Brigham, he says, taught him the winning textbook formula — painstaking attention to detail, exacting knowledge of the latest in business theory and practice, and a focus on clarity and simplification. “He’s been a terrific mentor.”

Brigham is equally appreciative. “I was very lucky to find some outstanding young professors who thought the same way I did,” he says, “and as a result the books are still going strong.”

**

Between teaching, writing, consulting and running the Public Utility Research Center, “I was spending 140 percent of my time doing stuff,” says Brigham. “But I really enjoyed it. You talk to people and they’re just waiting to retire. I couldn’t identify with that.”

Brigham did retire, but incrementally, officially leaving UF in 1995 to free up a position, but teaching without pay until 2002. He peeled away the consultant role next, and then the writing, only fully retiring in 2010.

He doesn’t live in the grandeur one would expect of a textbook czar, but his large apartment at Oak Hammock in Gainesville is airy and attractive. He is in robust health, having only quit running a few years ago. He watches TV on an exercise bike and hits the gym four days a week. Sue passed away in 2016, and he shares his home with a large and affectionate geriatric Doberman named Chocolate Chip IV.

Brigham has given generously to UF. Not, he insists, out of any desire to leave a legacy but because it seems the right thing to do. “I was successful, and the University of Florida was largely responsible for that success,” he says. “I want to do what I can to pay the university back.”

After all, he’s been the beneficiary of a huge amount of luck.

“Somebody can flip coins and hit tails 10 times. It’s pretty unusual to have happen.” He chuckles. “I hit tails 10 times.”